SMHS MethodsHeterogeneity

Scientific Methods for Health Sciences - Methods for Studying Heterogeneity of Treatment Effects, Case-Studies of Comparative Effectiveness Research

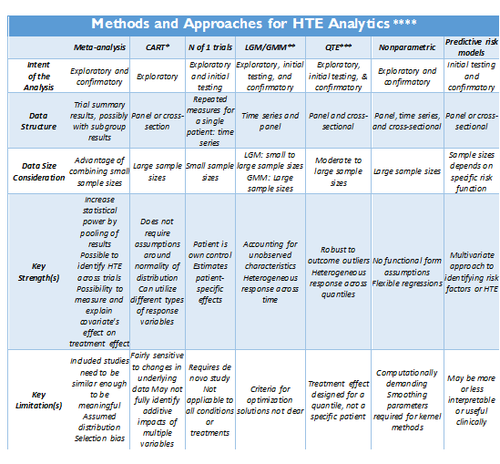

Adopted from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-12-185

- *CART: Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis

- ** LGM/GMM: Latent growth modeling/Growth mixture modeling.

- *** QTE: Quantile Treatment Effect.

- **** Standard meta-analysis like fixed and random effect models, and tests of heterogeneity, together with various plots and summaries, can be found in the R-package <bn>rmeta (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rmeta). Non-parametric R approaches are included in the np package, http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/np/vignettes/np.pdf.

Methods Summaries

Overview

Recursive partitioning is a data mining technique for exploring structure and patterns in complex data. It facilitates the visualization of decision rules for predicting categorical (classification tree) or continuous (regression tree) outcome variables. The R rpart package provides the tools for Classification and Regression Tree (CART) modeling, conditional inference trees, and random forests. Additional resources include an Introduction to Recursive Partitioning Using the RPART Routines . The Appendix includes description of the main CART analysis steps.

install.packages("rpart")

library("rpart")

I. CART (Classification and Regression Tree) is a decision-tree based technique that considers how variation observed in a given response variable (continuous or categorical) can be understood through a systematic deconstruction of the overall study population into subgroups, using explanatory variables of interest. For HTE analysis, CART is best suited for early-stage, exploratory analyses. Its relative simplicity can be powerful in identifying basic relationships between variables of interest, and thus identify potential subgroups for more advanced analyses. The key to CART is its ‘systematic’ approach to the development of the subgroups, which are constructed sequentially through repeated, binary splits of the population of interest, one explanatory variable at a time. In other words, each ‘parent’ group is divided into two ‘child’ groups, with the objective of creating increasingly homogeneous subgroups. The process is repeated and the subgroups are then further split, until no additional variables are available for further subgroup development. The resulting tree structure is oftentimes overgrown, but additional techniques are used to ‘trim’ the tree to a point at which its predictive power is balanced against issues of over-fitting. Because the CART approach does not make assumptions regarding the distribution of the dependent variable, it can be used in situations where other multivariate modeling techniques often used for exploratory predictive risk modeling would not be appropriate – namely in situations where data are not normally distributed.

CART analyses are useful in situations where there is some evidence to suggest that HTE exists, but the subgroups defining the heterogeneous response are not well understood. CART allows for an exploration of response in a myriad of complex subpopulations, and more recently developed ensemble methods (such as Bayesian Additive Regression Trees) allow for more robust analyses through the combination of multiple CART analyses.

Example Fifth Dutch growth study

# Let’s use the Fifth Dutch growth study (2009) fdgs . Is it true that “the world’s tallest nation has stopped growing taller: the height of Dutch children from 1955 to 2009”?

#install.packages("mice")

library("mice")

?fdgs

head(fdgs)

| ID | Reg | Age | Sex | HGT | WGT | HGT.Z | WGT.Z | |

| 1 | 100001 | West | 13.09514 | boy | 175.5 | 75.0 | 1.751 | 2.410 |

| 2 | 100003 | West | 13.81793 | boy | 148.4 | 40.0 | 2.292 | 1.494 |

| 3 | 100004 | West | 13.97125 | boy | 159.9 | 46.5 | 0.743 | 0.783 |

| 4 | 100005 | West | 13.98220 | girl | 159.7 | 46.5 | 0.743 | 0.783 |

| 5 | 100006 | West | 13.52225 | girl | 160.3 | 47.8 | 0.414 | 0.355 |

| 6 | 100018 | East | 10.21492 | boy | 157.8 | 39.7 | 2.025 | 0.823 |

summary(fdgs) summary(fdgs)

| ID | Reg | Age | Sex | HGT |

| Min.:100001 | North:732 | Min.:0.008214 | boy:4829 | Min.:46.0 |

| 1st Qu.:106353 | East:2528 | 1st Qu.:1.618754 | girl:5201 | 1st Qu.:83.8 |

| Median:203855 | South:2931 | Median:8.084873 | Median:131.5 | |

| Mean:180091 | West:2578 | Mean:8.157936 | Mean:123.9 | |

| 3rd Qu.210591 | City:1261 | 3rd Qu.:13.547570 | 3rd Qu.:162.3 | |

| Max:401955 | Max.:21.993155 | Max.:208.0 | ||

| NA's: 23 |

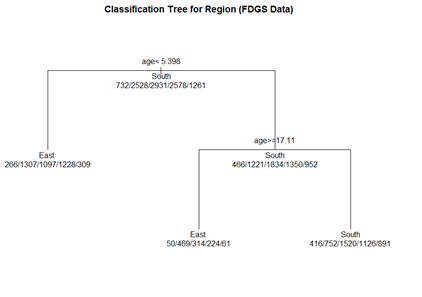

(1) Classification Tree

Let's use the data frame fdgs to predict Region, from Age, Height, and Weight.

# grow tree fit.1 <- rpart(reg ~ age + hgt + wgt, method="class", data= fdgs[,-1])

printcp(fit.1) # display the results plotcp(fit.1) # visualize cross-validation results summary(fit.1) # detailed summary of splits

# plot tree par(oma=c(0,0,2,0)) plot(fit.1, uniform=TRUE, margin=0.3, main="Classification Tree for Region (FDGS Data)") text(fit.1, use.n=TRUE, all=TRUE, cex=1.0)

# create a better plot of the classification tree post(fit.1, title = "Classification Tree for Region (FDGS Data)", file = "")

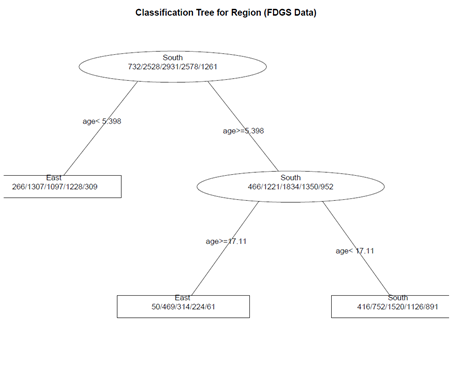

(2) Pruning the tree

pruned.fit.1<- prune(fit.1, cp= fit.1$\$$cptable[which.min(fit.1$\$$\$$cptable[,"xerror"]),"CP"])

# plot the pruned tree

plot(pruned.fit.1, uniform=TRUE, main="Pruned Classification Tree for Region (FDGS Data)")

text(pruned.fit.1, use.n=TRUE, all=TRUE, cex=1.0)

post(pruned.fit.1, title = "Pruned Classification Tree for Region (FDGS Data)")

Not much change, as the initial tree is not complex!

3) Random Forests

Random forests may improve predictive accuracy by generating a large number of bootstrapped trees (based on random samples of variables). It classifies cases using each tree in this new "forest", and decides the final predicted outcome by combining the results across all of the trees (an average in regression, a majority vote in classification). See the <b>randomForest</b> package.

library(randomForest)

fit.2 <- randomForest(reg ~ age + hgt + wgt, method="class", na.action = na.omit, data= fdgs[,-1])

print(fit.2) # view results

importance(fit.2) # importance of each predictor

Note on missing values/incomplete data: If the data have missing values, we have 3 choices:

1. Use a different tool (rpart handles missing values well)

2. Impute the missing values

3. For a small number of missing cases, we can use na.action = na.omit

==='"`UNIQ--h-2--QINU`"'Latent growth and growth mixture modeling (LGM/GMM)===

LGM and GMM represent structural equation modeling techniques that capture inter-individual differences in longitudinal change corresponding to a particular treatment. For instance, patients’ different timing patterns of the treatment effects may represent the underlying sources of HTE. LGM distinguish if (yes/no) and how (fast/slow, temporary/lasting) patients respond to treatment. The heterogeneous individual growth trajectories are estimated from intra-individual changes over time by examining common population parameters, i.e., slopes, intercepts, and error variances. Suppose each individual has unique initial status (intercept) and response rate (slope) during a specific time interval. Then the variances of the individuals’ baseline measures (intercepts) and changes (slopes) in health outcomes will represent the degree of HTE. The LGM-identified HTE of individual growth curves can be attributed to observed predictors, including both fixed and time varying covariates.

LGM assumes that all individuals are from the same population (too restrictive in some cases). If the HTE is due to observed demographic variables, such as age, gender, and marital status, one may utilize multiple-group LGM. Despite its successful applications for modeling longitudinal change, there may be multiple subpopulations with unobserved heterogeneities. Growth mixture modeling (GMM) extends LGM to allow the identification and prediction of unobserved subpopulations in longitudinal data analysis. Each unobserved subpopulation may constitute its own latent class and behave differently than individuals in other latent classes. Within each latent class, there are also different trajectories across individuals; however, different latent classes don’t share common population parameters. Suppose we are interested in studying retirees’ psychological well-being change trajectory when multiple unknown subpopulations exist. We can add another layer (a latent class variable) on the LGM framework so that the unobserved latent classes can be inferred from the data. The covariates in GMM are designed to affect growth factors distinctly across different latent classes. Therefore, there are two types of HTE: 1) the latent class variable in GMM divides individuals into groups with different growth curves; and 2) coefficient estimates vary across latent classes.

<b>Latent variables</b> are not directly observed – they are inferred (via a model) from other actually observed and directly measured variables. Models that explain observed variables in terms of latent variables are called latent variable models. Then the latent (unobserved) variable is discrete, it’s referred to as <b>latent class variable.</b>

Breast Cancer Example: Recall the LMER package, earlier review discussions, where Linear Mixed Model (LMM) are used for longitudinal data to examine change over time of outcomes according relative to predictive covariates. LMM assumptions include:

(i) continuous longitudinal outcome

(ii) Gaussian random-effects and errors

(iii) linearity of the relationships with the outcome

(iv) homogeneous population

(v) missing at random data

The objectives of LGM/GMM models (see <b>Latent Class Mixed Models, lcmm</b> R package) are to extend the linear mixed model estimation to:

(i) heterogeneous populations (relax (iv) above). Use <mark><b>hlme</b> for latent class linear mixed models</mark> (i.e. Gaussian continuous outcome)

(ii) other types of longitudinal outcomes : ordinal, (bounded) quantitative non-Gaussian outcomes (relax (i), (ii), (iii), (iv)). Use <b>lcmm</b> for general latent class mixed models with outcomes of different nature

(iii) joint analysis of a time-to-event (relax (iv), (v)). Use <b>Jointlcmm</b> for joint latent class models with a longitudinal outcome and a right-censored (left-truncated) time-to-event

Let’s use these data (http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/data/hdp.csv), representing cancer phenotypes and predictors (e.g., "IL6", "CRP", "LengthofStay", "Experience") and outcome measures (e.g., remission) collected on patients, nested within doctors (DID) and within hospitals (HID).

We can illustrate the latent class linear mixed models implemented in <b>hlme</b> through a study of the quadratic trajectories of the response (remission) with TumorSize, adjusting for CO2*Pain interaction and assuming correlated random-effects for the functions of SmokingHx and Sex. To estimate the corresponding standard linear mixed model using 1 latent class where CO2 interacts with Pain:

# install.packages("lcmm")

library("lcmm")

hdp <- read.csv("http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/data/hdp.csv")

hdp <- within(hdp, {

Married <- factor(Married, levels = 0:1, labels = c("no", "yes"))

DID <- factor(DID)

HID <- factor(HID)

})

add a new subject ID column (last column in the data, “ID”), this is necessary for the hmle call

hdp$\$$ID <- seq.int(nrow(hdp))

model.hlme <- hlme(remission ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay + Experience + I(tumorsize^2) + co2*pain + I(tumorsize^2)*pain, random=~ SmokingHx + Sex, subject='ID', data=hdp, ng=1) summary(model.hlme)

Heterogenous linear mixed model fitted by maximum likelihood method hlme(fixed = remission ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay + Experience + I(tumorsize^2) + co2 * pain + I(tumorsize^2) * pain, random = ~SmokingHx + Sex, subject = "ID", ng = 1, data = hdp) Statistical Model: Dataset: hdp Number of subjects: 8525 Number of observations: 8525 Number of latent classes: 1 Number of parameters: 21 Iteration process: Convergence criteria satisfied Number of iterations: 34 Convergence criteria: parameters= 1.2e-09 : likelihood= 8.3e-06 : second derivatives= 2.7e-05 Goodness-of-fit statistics: maximum log-likelihood: -5223.9 AIC: 10489.79 BIC: 10637.86

Maximum Likelihood Estimates:

| coef | Se | Wald | p-value | |

| Intercept | 0.28636 | 0.24314 | 1.178 | 0.23890 |

| IL6 | -0.01134 | 0.00183 | -6.184 | 0.00000 |

| CRP | -0.00674 | 0.00167 | -4.043 | 0.00005 |

| LengthofStay | -0.04834 | 0.00463 | -10.436 | 0.00000 |

| Experience | 0.01695 | 0.00119 | 14.263 | 0.00000 |

| I(tumorsize^2) | 0.00000 | 0.00001 | -0.076 | 0.93953 |

| co2 | -0.03549 | 0.16204 | -0.219 | 0.82663 |

| pain | 0.03930 | 0.04278 | 0.919 | 0.35832 |

| co2:pain | -0.01489 | 0.02871 | -0.519 | 0.60395 |

| I(tumorsize^2):pain | 0.00000 | 0.00000 | 0.553 | 0.58045 |

| intercept | SmokingHxformer | SmokingHxnever | Sexmale | |

| intercept | 0.19310943 | |||

| SmokingHxformer | -0.10617988 | 0.209155186 | ||

| SmokingHxnever | -0.12388534 | 0.068342049 | 2.262655e-01 | |

| Sexmale | -0.08130975 | -0.007353491 | -1.873934e-05 | 0.1730187 |

Residual standard error:

coef: 0.1299767

se: 1.187426

Results interpretation:

(1) The first part of the summary provides information about the dataset, the number of subjects, observations, observations deleted (since by default, missing observations are deleted), number of latent classes and number of parameters.

(2) Next, details about the algorithm convergence is provided along with the number of iterations, the convergence criteria, and the information indicating if the model converged correctly: "convergence criteria satisfied".

(3) The maximum log-likelihood, Akaike criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information criterion (BIC) are reported.

(4) Estimates of parameters, the estimated standard error, the Wald Test statistics (with Normal approximation) and the corresponding p-values are reported below.

(5) For the random-effect distribution, the estimated matrix of covariance of the random-effects is displayed.

(6) The standard error of the residuals is given along with its estimated standard error.

(7) The effect of TumorSize seems not associated with change over Pain of Remission. This may be formally assessed using a multivariate Wald test:

WaldMult(model.hlme, pos=c(6,8)) # pos - a vector containing the indices in model.hlme of the parameters to test Wald Test p_value I(tumorsize^2) = pain = 0 0.85562 0.65193

We may consider the model with an adjustment for CRP only on the intercept. Below we estimate the corresponding models for a varying number of latent classes (from 1 to 3) using the default initial values:

# Initial Model: model.hlme <- hlme(remission ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay + Experience + I(tumorsize^2) + co2*pain + I(tumorsize^2)*pain, random=~ SmokingHx + Sex, subject='ID', data=hdp, ng=1)

model.hlme.1 <- hlme(tumorsize ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay, subject='ID', data=hdp, ng=1) model.hlme.2 <- hlme(tumorsize ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay + SmokingHx, mixture=~ SmokingHx, subject='ID', data=hdp, ng=2) model.hlme.3 <- hlme(tumorsize ~ IL6 + CRP + LengthofStay + SmokingHx, mixture=~ SmokingHx, subject='ID', data=hdp, ng=3)

The estimation process for a varying number of latent classes can be summarized with summarytable, which gives the log-likelihood, the number of parameters, the Bayesian Information Criterion, and the posterior proportion of each class:

summarytable(model.hlme.1, model.hlme.2, model.hlme.3)

G loglik npm BIC %class1 %class2 %class3

model.hlme.1 1 -33301.82 5 66648.89 100.000000

model.hlme.2 2 -31592.79 11 63285.15 99.214076 0.7859238

model.hlme.3 3 -31589.55 15 63314.86 6.357771 82.2991202 11.34311

The program took 404.65 seconds)

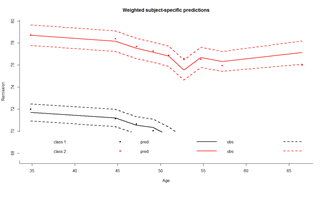

In this example, the optimal number of latent classes according to the BIC is two (the smallest BIC). The posterior classification is described with:

postprob(model.hlme.2)

Posterior classification:

class1 class2

N 8458.00 67.00

% 99.21 0.79

Posterior classification table:

--> mean of posterior probabilities in each class

prob1 prob2

class1 0.8555 0.1445

class2 0.4362 0.5638

Posterior probabilities above a threshold (%):

class1 class2

prob>0.7 92.48 2.99

prob>0.8 77.38 0.00

prob>0.9 38.53 0.00

In this example, the first class includes a posteriori 8458 subjects (99%) while class 2 includes 67 (0.79%) subjects. Subjects were classified in class 1 with a mean posterior probability of 0.8555 %.

In class 1, 92.48% were classified with a posterior probability above 0.7 while 2.99% of the subjects were classified in class 2 with a posterior probability above 0.7. Goodness-of-fit of the model can be assessed by displaying the residuals as in figure and the mean predictions of the model as in figure, according to the time variable given in var.time:

plot(model.hlme.2) # Figure (left panel) plot(model.hlme.2, which="fit", var.time="Age", bty="l", ylab=" Remission ", xlab="Age", lwd=2) # Figure (right panel) plot(model.hlme.2, which="fit", var.time="Age", bty="l", ylab=" Remission ", xlab="Age", lwd=2, marg=FALSE)

The latent process mixed models implemented in lcmm are illustrated through the study of the linear trajectory of ntumors with Age adjusted for Sex and assuming correlated random-effects for the intercept and Age. Lines estimate the corresponding latent process mixed model with different link functions:

model.hlme.lin <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age ,subject='ID', data=hdp) model.hlme.beta <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age, subject='ID', data=hdp, link='beta') model.hlme.spl <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age, subject='ID', data=hdp, link='splines') model.hlme.spl5q <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age, subject='ID', data=hdp, link='5-quant-splines')

link function: An optional family of link functions. By default,

- "linear" option specifies a linear link function leading to a standard linear mixed model (homogeneous or heterogeneous as estimated in hlme).

- "beta" for estimating a link function from the family of Beta cumulative distribution functions, "thresholds" for using a threshold model to describe the correspondence between each level of an ordinal outcome and the underlying latent process, and

- "Splines" for approximating the link function by I-splines. For this latter case, the number of nodes and the nodes location should be also specified. The number of nodes is first entered followed by,

- then the location is specified with "equi", "quant" or "manual" for respectively equidistant nodes, nodes at quantiles of the marker distribution or interior nodes entered manually in argument

- intnodes. It is followed by - and finally "splines" is indicated. For example, "7-equi-splines" means I-splines with 7 equidistant nodes, "6-quant-splines" means I-splines with 6 nodes located at the quantiles of the marker distribution and "9-manual-splines" means I-splines with 9 nodes, the vector of 7 interior nodes being entered in the argument intnodes.

summary (model.hlme.lin)

General latent class mixed model fitted by maximum likelihood method

lcmm(fixed = ntumors ~ Age * Sex, random = ~Age, subject = "ID",data = hdp)

Statistical Model:

Dataset: hdp

Number of subjects: 8525

Number of observations: 8525

Number of latent classes: 1

Number of parameters: 8

Link function: linear

Iteration process:

Maximum number of iteration reached without convergence

Number of iterations: 100

Convergence criteria: parameters= 5.4e-10

: likelihood= 5.5e-10

: second derivatives= 1

Goodness-of-fit statistics:

maximum log-likelihood: -19915.24

AIC: 39846.49

BIC: 39902.89

Discrete posterior log-likelihood: 0

Discrete AIC: 16

Mean discrete AIC per subject: 9e-04

Mean UACV per subject: 0

Mean discrete LL per subject: 0

Maximum Likelihood Estimates:

Fixed effects in the longitudinal model:

coef Se Wald p-value intercept (not estimated) 0.00000 Age 0.09491 Sexmale -0.66303 Age:Sexmale 0.01132

Variance-covariance matrix of the random-effects:

intercept Age

intercept 20.5013715

Age -0.2889814 0.007696382

Residual standard error (not estimated) = 1

Parameters of the link function:

coef Se Wald p-value Linear 1 (intercept) -0.36768 Linear 2 (std err) 0.71432

Objects mlin, mbeta, mspl and mspl3eq are latent process mixed models that assume the exact same trajectory for the underlying latent process but respectively a linear, BetaCDF, I-splines with 5 equidistant knots (default with link=’splines’) and I-splines with 5 knots at percentiles. mlin reduces to a standard linear mixed model (link=’linear’ by default). The only difference with a hlme object is the parameterization for the intercept and the residual standard error that are considered as rescaling parameters.

col <- rainbow(4)

plot(model.hlme.lin, which="linkfunction", bty='l', ylab="Number-of-Tumors", col=col[1], lwd=2, xlab="underlying latent process")

plot(model.hlme.beta, which="linkfunction", add=T, col=col[2], lwd=2)

plot(model.hlme.spl, which="linkfunction", add=T, col=col[3], lwd=2)

plot(model.hlme.spl5q, which="linkfunction", add=T, col=col[4], lwd=2)

legend(x="topleft",legend=c("linear", "beta","splines (5equidistant)", "splines (5 at quantiles)"), lty=1,col=col,bty="n",lwd=2)

# to obtain confidence bands use function predictlink link.lin <- predictlink(model.hlme.lin, ndraws=2000)

Error in predictlink.lcmm(model.hlme.spl, ndraws = 2000): No confidence intervals can be produced since the program did not converge properly

model.hlme.lin$\$$conv <mark># double-check the convergence of the algorithm[1] 2</mark></span>

<span style="color:#ff0000"># status of convergence:</span>

<span style="color:#ff0000"># =1 if the convergence criteria were satisfied,</span>

<span style="color:#ff0000"># =2 if the maximum number of iterations was reached,</span>

<span style="color:#ff0000"># =4 or 5 if a problem occured during optimisation</span>

model.hlme.lin <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age ,subject='ID', epsY = 0.5, convB = 1e-01, convL = 1e-01, <mark>convG = 1e-01</mark>, maxiter=200, data=hdp); model.hlme.lin$conv

<mark># Now that we have convergence, we can obtain CI’s!!!</mark>

link.lin <- predictlink(model.hlme.lin, ndraws=2000)

# plot(model.hlme.lin, which="linkfunction", bty='l', ylab="Number-of-Tumors", col=col[1], lwd=2, xlab="underlying latent process")

plot(link.lin, add=TRUE, col=col[1], lty=2, lwd=2)

legend(x="left", legend=c("95% confidence bands", "for linear fit"), lty=c(2,NA), col=c(col[1],NA), bty="n", lwd=2)

<center>[[Image:SMHS_Methods7.png|500px]] </center>

# <mark>Repeat using the other link functions … model.hlme.beta, model.hlme.spl, …</mark>

model.hlme.beta <- lcmm(ntumors ~ Age*Sex, random=~ Age, subject='ID', data=hdp, link='beta',

<mark>convB = 1e-01</mark>, convL = 1e-01, convG = 1e-01, maxiter=200); model.hlme.beta$\$$conv

link.beta <- predictlink(model.hlme.beta, ndraws=2000)

plot(link.beta, add=TRUE, col=col[2], lty=2, lwd=2)

legend(x="left", legend=c("95% confidence bands", "for BETA fit"), lty=c(3,NA), col=c(col[2],NA), bty="n", lwd=1)

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis is an approach to combine treatment effects across trials or studies into an aggregated treatment effect with higher statistical power than observed in each individual trials. It may detect HTE by testing for differences in treatment effects across similar RCTs. It requires that the individual treatment effects are similar to ensure pooling is meaningful. In the presence of large clinical or methodological differences between the trials, it may be to avoid meta-analyses. The presence of HTE across studies in a meta-analysis may be due to differences in the design or execution of the individual trials (e.g., randomization methods, patient selection criteria). Cochran's Q is a methods for detection of heterogeneity, which is computed as the weighted sum of squared differences between each study's treatment effect and the pooled effects across the studies. It is a barometer of inter-trial differences impacting the observed study result. A possible source of error in a meta-analysis is publication bias. Trial size may introduce publication bias since larger trials are more likely to be published. Language and accessibility represent other potential confounding factors. When the heterogeneity is not due to poor study design, it may be useful to optimize the treatment benefits for different cohorts of participants.

Cochran's Q statistics is the weighted sum of squares on a standardized scale. The corresponding P value indicates the strength of the evidence of presence of heterogeneity. This test may have low power to detect heterogeneity sometimes and it is suggested to use a value of 0.10 as a cut-off for significance (Higgins et al., 2003). The Q statistics also may have too much power as a test of heterogeneity when the number of studies is large.

Simulation Example 1

# Install and Load library

install.packages("meta")

library(meta)

# Set number of studies

n.studies = 15

# number of treatments: case1, case2, control

n.trt = 3

# number of outcomes

n.event = 2

# simulate the (balanced) number of cases (case1 and case2) and controls in each study

ctl.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = 200, prob = 0.3)

case1.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = 200, prob = 0.3)

case2.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = 200, prob = 0.3)

# Simulate the number of outcome events (e.g., deaths) and no events in the control group event.ctl.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = ctl.group, prob = rep(0.1, length(ctl.group))) noevent.ctl.group = ctl.group - event.ctl.group # Simulate the number of events and no events in the case1 group event.case1.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = case1.group, prob = rep(0.5, length(case1.group))) noevent.case1.group = case1.group - event.case1.group

# Simulate the number of events and no events in the case2 group event.case2.group = rbinom(n = n.studies, size = case2.group, prob = rep(0.6, length(case2.group))) noevent.case2.group = case2.group - event.case2.group

# Run the univariate meta-analysis using metabin(), Meta-analysis of binary outcome data – # Calculation of fixed and random effects estimates (risk ratio, odds ratio, risk difference or arcsine # difference) for meta-analyses with binary outcome data. Mantel-Haenszel (MH), # inverse variance and Peto method are available for pooling.

# method = A character string indicating which method is to be used for pooling of studies. # one of "MH" , "Inverse" , or "Cochran" # sm = A character string indicating which summary measure (“OR”, "RR" "RD"=risk difference) is to be # used for pooling of studies

# Control vs. Case1, n.e and n.c are numbers in experimental and control groups meta.ctr_case1 <- metabin(event.e = event.case1.group, n.e = case1.group, event.c = event.ctl.group, n.c = ctl.group, method = "MH", sm = "OR") # in this case we use Odds Ratio, of the odds of death in the experimental and control studies forest(meta.ctr_case1)

# Control vs. Case2 meta.ctr_case2 <- metabin(event.e = event.case2.group, n.e = case2.group, event.c = event.ctl.group, n.c = ctl.group, method = "MH", sm = "OR") forest(meta.ctr_case2)

# Case1 vs. Case2 meta.case1_case2 <- metabin(event.e = event.case1.group, n.e = case1.group, event.c = event.case2.group, n.c = case2.group, method = "MH", sm = "OR") forest(meta.case1_case2) summary(meta.case1_case2)

Test of heterogeneity:

Q d.f. p-value

11.99 14 0.6071

The forest plot shows the I2 test indicates the evidence to reject the null hypothesis (no study heterogeneity and the fixed effects model should be used).

Series of “N of 1” trials

This technique combines (a “series of”) n-of-1 trial data to identify HTE. An n-of-1 trial is a repeated crossover trial for a single patient, which randomly assigns the patient to one treatment vs. another for a given time period, after which the patient is re-randomized to treatment for the next time period, usually repeated for 4-6 time periods. Such trials are most feasibly done in chronic conditions, where little or no washout period is needed between treatments and treatment effects are identifiable in the short-term, such as pain or reliable surrogate markers. Combining data from identical n-of-1 trials across a set of patients enables the statistical analysis controlling for patient fixed or random effects, covariates, centers, or sequence effects, see Figure below. These combined trials are often analyzed within a Bayesian context using shrinkage estimators that combine individual and group mean treatment effects to create a “posterior” individual mean treatment effect estimate which is a form of inverse variance-weighted average of the individual and group effects. Such trials are typically more expensive than standard RCTs on a per-patient basis, however, they require much smaller sample sizes, often less than 100 patients (due to the efficient individual-as-own-control design), and create individual treatment effect estimates that are not possible in a non-crossover design . For the individual patient, the treatment effect can be re-estimated after each time period, and the trial stopped at any point when the more effective treatment is identified with reasonable statistical certainty.

Example: A study involving 8 participants collected data across 30 days, in which 15 treatment days and 15 control days are randomly assigned within each participant . The treatment effect is represented as a binary variable (control day=0; treatment day=1). The outcome variable represents the response to the intervention within each of the 8 participants. Study employed a fixed-effects modeling. By creating N − 1 dummy-coded variables representing the N=8 participants, where the last (i=8) participant serves as the reference (i.e., as the model intercept). So, each dummy-coded variable represents the difference between each participant (i) and the 8th participant. Thus, all other patients' values will be relative to the values of the 8th (reference) subject. The overall differences across participants in fixed effects can be evaluated with multiple degree-of-freedom F-tests.

| ID | Day | Tx | SelfEff | SelfEff25 | WPSS | SocSuppt | PMss | PMss3 | PhyAct |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 8 | 0.97 | 5.00 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 53 |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 8 | -0.17 | 3.87 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 73 |

| 1 | 3 | 0 | 33 | 8 | 0.81 | 4.84 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 23 |

| 1 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 8 | -0.41 | 3.62 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 36 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

Complete data is available in the Appendix.

| Intercept | Constant |

| Physical Activity | PhyAct |

| Intervention | Tx |

| WP Social Support | WPSS |

| PM Social Support (1-3) | PMss3 |

| Self Efficacy | SelfEff25 |

rm(list=ls())

Nof1 <-read.table("https://umich.instructure.com/files/330385/download?download_frd=1&verifier=DwJUGSd6t24dvK7uYmzA2aDyzlmsohyaK6P7jK0Q", sep=",", header = TRUE) # 02_Nof1_Data.csv

attach(Nof1)

head(Nof1)

| ID | Day | Tx | SelfEff | SelfEff25 | WPSS | SocSuppt | PMss | PMss3 | PhyAct | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 8 | 0.97 | 5.00 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 53 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 8 | -0.17 | 3.87 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 73 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 33 | 8 | 0.81 | 4.84 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 23 |

| 4 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 8 | -0.41 | 3.62 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 36 |

| 5 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 33 | 8 | 0.59 | 4.62 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 21 |

| 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 33 | 8 | -1.16 | 2.87 | 4.03 | 1.03 | 0 |

df.1 = data.frame(PhyAct, Tx, WPSS, PMss3, SelfEff25)

# library("lme4")

lm.1 = model.lmer <- lmer(PhyAct ~ Tx + SelfEff + Tx*SelfEff + (1|Day) + (1|ID) , data= df.1) summary(lm.1)

Linear mixed model fit by REML ['lmerMod'] Formula: PhyAct ~ Tx + SelfEff + Tx * SelfEff + (1 | Day) + (1 | ID) Data: df.1

REML criterion at convergence: 8820

| Min | 1Q | Median | 3Q | Max |

| Groups | Name | Variance | Std.Dev. |

| Day | (Intercept) | 0.0 | 0.00 |

| ID | (Intercept) | 601.5 | 24.53 |

| Residual | 969.0 | 31.13 |

Number of obs: 900, groups: Day, 30; ID, 30

| Estimate | Std. | Error | t value |

| (Intercept) | 38.3772 | 14.4738 | 2.651 |

| Tx | 4.0283 | 6.3745 | 0.632 |

| SelfEff | 0.5818 | 0.5942 | 0.979 |

| Tx:SelfEff | 0.9702 | 0.2617 | 3.708 |

| (Intr) | Tx | SlfEff | |

| Tx | -0.220 | ||

| SelfEff | -0.946 | 0.208 | |

| Tx:SelfEff | 0.208 | -0.946 | -0.220 |

# Model: PhyAct = Tx + WPSS + PMss3 + Tx*WPSS + Tx*PMss3 + SelfEff25 + Tx*SelfEff25 + ε lm.2 = lm(PhyAct ~ Tx + WPSS + PMss3 + Tx*WPSS + Tx*PMss3 + SelfEff25 + Tx*SelfEff25, df.1) summary(lm.2)

Call: lm(formula = PhyAct ~ Tx + WPSS + PMss3 + Tx * WPSS + Tx * PMss3 + SelfEff25 + Tx * SelfEff25, data = df.1)

| Min | 1Q | Median | 3Q | Max |

| -102.39 | -28.24 | -1.47 | 25.16 | 122.41 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t value | t|)$ | |

| (Intercept) | 52.0067 | 1.8080 | 28.764 | < 2e-16 *** |

| Tx | 27.7366 | 2.5569 | 10.848 | < 2e-16 *** |

| WPSS | 1.9631 | 2.4272 | 0.809 | 0.418853 |

| PMss3 | 13.5110 | 2.7853 | 4.851 | 1.45e-06 *** |

| SelfEff25 | 0.6289 | 0.2205 | 2.852 | 0.004439 ** |

| Tx:WPSS | 9.9114 | 3.4320 | 2.888 | 0.003971 ** |

| Tx:PMss3 | 8.8422 | 3.9390 | 2.245 | 0.025025 * |

| Tx:SelfEff25 | 1.0460 | 0.3118 | 3.354 | 0.000829 ***

|

[Using SAS (StudyI_Analyses.sas, StudyIIab_Analyses.sas)]

| Effect | Num DF | Den DF | F Value | $Pr>F$ |

| Tx | 1 | 224 | 67.46 | <.0001 |

| ID | 7 | 224 | 25.95 | <.0001 |

| Tx*ID | 7 | 224 | 2.92 | 0.0060 |

Quantile Treatment Effect (QTE)

QTE employs quantile regression estimation (QRE) to examine the central tendency and statistical dispersion of the treatment effect in a population. These may not be revealed by the conventional mean estimation in RCTs. For instance, patients with different comorbidity scores may respond differently to a treatment. Quantile regression has the ability to reveal HTE according to the ranking of patients’ comorbidity scores or some other relevant covariate by which patients may be ranked. Therefore, in an attempt to inform patient-centered care, quantile regression provides more information on the distribution of the treatment effect than typical conditional mean treatment effect estimation. QTE characterizes the heterogeneous treatment effect on individuals and groups across various positions in the distributions of different outcomes of interest. This unique feature has given quantile regression analysis substantial attention and has been employed across a wide range of applications, particularly when evaluating the economic effects of welfare reform.

One caveat of applying QRE in clinical trials for examining HTE is that the QTE doesn’t demonstrate the treatment effect for a given patient. Instead, it focuses on the treatment effect among subjects within the qth quantile, such as those who are exactly at the top 10th percent in terms of blood pressure or a depression score for some covariate of interest, for example, comorbidity score. It is not uncommon for the qth quantiles to be two different sets of patients before and after the treatment. For this reason, we have to assume that these two groups of patients are homogeneous if they were in the same quantiles.

Income-Food Expenditure Example: Let’s examine the Engel data (N=235) on the relationship between food expenditure (foodexp) and household income (income). We can plot the data and then explore the superposition of the six fitted quantile regression lines.

install.packages("quantreg")

library(quantreg)

data(engel)

attach(engel)

|}

| Income | Foodexp | |

| 1 | 420.1577 | 255.8394 |

| 2 | 541.4117 | 310.9587 |

| 3 | 901.1575 | 485.6800 |

| 4 | 639.0802 | 402.9974 |

| 5 | 750.8756 | 495.5608 |

| 6 | 945.7989 | 633.7978 |