Difference between revisions of "AP Statistics Curriculum 2007 Prob Rules"

m (→Contingency table) |

m (Text replacement - "{{translate|pageName=http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/" to ""{{translate|pageName=http://wiki.socr.umich.edu/") |

||

| (34 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

=== Addition Rule=== | === Addition Rule=== | ||

| + | Let's start with an example. Suppose the chance of colder weather (C) is 30%, chance of rain (R) and colder weather (C) is 15% and the chance of rain or colder weather is 75%. What is the chance of rain. This can be computed by observing that \(P(R \cup C) = P(R) + P(C) - P(R \cap C)\). Thus, \(P(R) = P(R \cup C) − P(C) + P(R \cap C)= 0.75 − 0.3 + 0.15 = 0.6\). How can this observation be generalized? | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

The probability of a union, also called the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusion-exclusion_principle Inclusion-Exclusion principle] allows us to compute probabilities of composite events represented as unions (i.e., sums) of simpler events. | The probability of a union, also called the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inclusion-exclusion_principle Inclusion-Exclusion principle] allows us to compute probabilities of composite events represented as unions (i.e., sums) of simpler events. | ||

[[Image:500px-Inclusion-exclusion.svg.png|150px|thumbnail|right| [http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Inclusion-exclusion.svg/180px-Inclusion-exclusion.svg.png Venn Diagrams]]] | [[Image:500px-Inclusion-exclusion.svg.png|150px|thumbnail|right| [http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/42/Inclusion-exclusion.svg/180px-Inclusion-exclusion.svg.png Venn Diagrams]]] | ||

| Line 13: | Line 16: | ||

In general, for any ''n'', | In general, for any ''n'', | ||

:<math>P(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_i) =\sum_{i=1}^n {P(A_i)} | :<math>P(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_i) =\sum_{i=1}^n {P(A_i)} | ||

| − | -\sum_{i,j\,:\,i<j}{P(A_i\cap A_j)} +\sum_{i,j,k\,:\,i<j<k}{P(A_i\cap A_j\cap A_k)}+ \cdots\cdots\ +(-1)^{m+1} \sum_{i_1<i_2< \cdots < i_m}{P(\bigcap_{p=1}^m A_{i_p})}+ \cdots\cdots\ +(-1)^{n+1} P(\bigcap_{i=1}^n A_i).</math> | + | -\sum_{i,j\,:\,i<j}{P(A_i\cap A_j)} +\sum_{i,j,k\,:\,i<j<k}{P(A_i\cap A_j\cap A_k)}+ \cdots</math> |

| + | :<math>\cdots\ +(-1)^{m+1} \sum_{i_1<i_2< \cdots < i_m}{P(\bigcap_{p=1}^m A_{i_p})}+ \cdots\cdots\ +(-1)^{n+1} P(\bigcap_{i=1}^n A_i).</math> | ||

===Conditional Probability=== | ===Conditional Probability=== | ||

| Line 22: | Line 26: | ||

* Also see [[SOCR_EduMaterials_Activities_CoinDieExperiment#Applications:_Conditional_Probability | demonstration of conditional probability using the SOCR Coin-Die Experiment]]. | * Also see [[SOCR_EduMaterials_Activities_CoinDieExperiment#Applications:_Conditional_Probability | demonstration of conditional probability using the SOCR Coin-Die Experiment]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Suppose X and Y are jointly continuous random variables with a joint density \(ƒ_{X,Y}(x,y)\). If ''A'' and ''B'' (non-trivial) are subsets of the ranges of X and Y (e.g., intervals), then: | ||

| + | : \( P(X \in A \mid Y \in B) = \frac{\int_{y\in B}\int_{x\in A} f_{X,Y}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}{\int_{y\in B}\int_{x\in\Omega} f_{X,Y}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}. \) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the special case where ''B''={''y''<sub>0</sub>}, representing a single point, the conditional probability is: | ||

| + | : \( P(X \in A \mid Y = y_0) = \frac{\int_{x\in A} f_{X,Y}(x,y_0)\,dx}{\int_{x\in\Omega} f_{X,Y}(x,y_0)\,dx}. \) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Of course, if the set (range) ''A'' is trivial, then the conditional probability is zero. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * See the example of the [http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/HTML5/BivariateNormal/ SOCR HTML5 Bivariate (2D) Normal Distribution Calculator] (webapp). | ||

| + | |||

| + | * The conditional probability distribution of X given Y = \(y_0\), \(f_{X|Y=y_o}\), is given by: | ||

| + | : \( f_{X|y_o} \sim N \left ( \mu_{X|y_o} = \mu_X +\rho \frac{\sigma_X}{\sigma_Y}(y_o-\mu_Y), \sigma_{X|y_o}^2 = \sigma_X^2(1-\rho^2) \right) \), where | ||

| + | :: \( X \sim N (\mu_X, \sigma_X^2) \), | ||

| + | :: \( Y \sim N (\mu_Y, \sigma_Y^2) \), and | ||

| + | :: \( \rho = Corr(X,Y)\) is the correlation between X and Y. | ||

| + | :: This [[SOCR_BivariateNormal_JS_Activity#Background| expression of the density assumes]] that the conditional mean of X given \(y_o\) is linear in y and the conditional variance of X given \(y_o\) is constant. | ||

===Examples=== | ===Examples=== | ||

====Contingency table==== | ====Contingency table==== | ||

| − | Here is the data | + | Here is the data of 400 Melanoma (skin cancer) Patients by Type and Site |

<center> | <center> | ||

{| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:75%" border="1" | {| class="wikitable" style="text-align:center; width:75%" border="1" | ||

| Line 45: | Line 66: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

| − | * Suppose we select one out of the 400 patients in the study and we want to find the probability that the cancer is on the extremities ''given'' that it is of | + | * Suppose we select one out of the 400 patients in the study and we want to find the probability that the cancer is on the extremities ''given'' that it is a type of nodular: P = 73/125 = P(Extremities | Nodular) |

* What is the probability that for a randomly chosen patient the cancer type is Superficial given that it appears on the Trunk? | * What is the probability that for a randomly chosen patient the cancer type is Superficial given that it appears on the Trunk? | ||

====Monty Hall Problem==== | ====Monty Hall Problem==== | ||

| − | Recall that earlier we discussed the [[AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Basics#Hands-on_activities | Monty Hall Experiment]]. We | + | Recall that earlier we discussed the [[AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Basics#Hands-on_activities | Monty Hall Experiment]]. We now show the odds of winning double if we use the swap strategy - that is the probability of a win is 2/3, if each time we switch and choose the last third card. |

Denote W={Final Win of the Car Price}. Let L<sub>1</sub> and W<sub>2</sub> represent the events of choosing the donkey (loosing) and the car (winning) at the player's first and second choice, respectively. Then, the chance of winning in the swapping-strategy case is: | Denote W={Final Win of the Car Price}. Let L<sub>1</sub> and W<sub>2</sub> represent the events of choosing the donkey (loosing) and the car (winning) at the player's first and second choice, respectively. Then, the chance of winning in the swapping-strategy case is: | ||

| − | <math>P(W) = P(L_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | L_1) P(L_1) = 1 \times {2\over 3} ={2\over 3}</math> | + | <math>P(W) = P(L_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | L_1) P(L_1) = 1 \times {2\over 3} ={2\over 3}.</math> If we played using the [[AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Basics#Hands-on_activities | stay-home strategy]], our chance of winning would have been: |

| − | <math>P(W) = P(W_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | W_1) P(W_1) = 1 \times {1\over 3} ={1\over 3}</math> | + | <math>P(W) = P(W_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | W_1) P(W_1) = 1 \times {1\over 3} ={1\over 3},</math> or half the chance in the first (swapping) case. |

====Drawing balls without replacement==== | ====Drawing balls without replacement==== | ||

| − | Suppose we draw 2 balls | + | Suppose we draw 2 balls randomly, one at a time without replacement from an urn containing 4 black and 3 white balls, otherwise identical. What is the probability that the second ball is black? Sample Space? |

P({2-nd ball is black}) = P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is black}) + P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is white}) = 4/7 x 3/6 + 4/6 x 3/7 = 4/7. | P({2-nd ball is black}) = P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is black}) + P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is white}) = 4/7 x 3/6 + 4/6 x 3/7 = 4/7. | ||

===Inverting the order of conditioning=== | ===Inverting the order of conditioning=== | ||

| − | In many practical situations | + | In many practical situations, it is beneficial to be able to swap the event of interest and the conditioning event when we are computing probabilities. This can easily be accomplished using this trivial, yet powerful, identity: |

<center> <math>P(A \cap B) = P(A | B) \times P(B) = P(B | A) \times P(A)</math></center> | <center> <math>P(A \cap B) = P(A | B) \times P(B) = P(B | A) \times P(A)</math></center> | ||

===Example - inverting conditioning=== | ===Example - inverting conditioning=== | ||

| − | Suppose we classify the entire female population into 2 | + | Suppose we classify the entire female population into 2 classes: healthy(NC) controls and cancer patients. If a woman has a positive mammogram result, what is the probability that she has breast cancer? |

| − | Suppose we obtain medical evidence for a subject in terms of the results of her mammogram (imaging) test: positive or negative mammogram . If P(Positive Test) = 0.107, P(Cancer) = 0.1, P(Positive test | Cancer) = 0.8, then we can easily calculate the probability of real interest - | + | Suppose we obtain medical evidence for a subject in terms of the results of her mammogram (imaging) test: positive or negative mammogram . If P(Positive Test) = 0.107, P(Cancer) = 0.1, P(Positive test | Cancer) = 0.8, then we can easily calculate the probability of real interest - the chance that the subject has cancer: |

<center><math>P(Cancer | Positive Test) = {P(Positive Test | Cancer) \times P(Cancer) \over P(Positive Test)}= {0.8\times 0.1 \over 0.107}</math> </center> | <center><math>P(Cancer | Positive Test) = {P(Positive Test | Cancer) \times P(Cancer) \over P(Positive Test)}= {0.8\times 0.1 \over 0.107}</math> </center> | ||

| − | This equation has 3 known parameters and 1 unknown variable | + | This equation has 3 known parameters and 1 unknown variable. So, we can solve for P(Cancer | Positive Test) to determine the chance the patient who has breast cancer given that her mammogram was positively read. This probability, of course, will significantly influence the treatment action recommended by the physician. |

===Statistical Independence=== | ===Statistical Independence=== | ||

| − | Events A and B are '''statistically independent''' | + | Events A and B are '''statistically independent'''. Even knowing whether B has occurred gives no new information about the chances of A occurring, i.e., if P(A | B) = P(A). |

Note that if A is independent of B, then B is also independent of A, i.e., P(B | A) = P(B), since <math>P(B|A)={P(B \cap A) \over P(A)} = {P(A|B)P(B) \over P(A)} = P(B)</math>. | Note that if A is independent of B, then B is also independent of A, i.e., P(B | A) = P(B), since <math>P(B|A)={P(B \cap A) \over P(A)} = {P(A|B)P(B) \over P(A)} = P(B)</math>. | ||

| Line 85: | Line 106: | ||

In general, for any collection of events: | In general, for any collection of events: | ||

| − | <center><math>P(A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_n) = P(A_1)P(A_2|A_1)P(A_3|A_1 \cap A_2)P(A_4|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3) \cdots P(A_{n-1}|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_{n-2})P(A_n|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_{n-1})</math></center> | + | <center><math>P(A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_n) = P(A_1)P(A_2|A_1)P(A_3|A_1 \cap A_2)P(A_4|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3) \cdots </math> |

| + | <math>\cdots P(A_{n-1}|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_{n-2})P(A_n|A_1 \cap A_2 \cap A_3 \cap \cdots \cap A_{n-1})</math></center> | ||

===Law of total probability=== | ===Law of total probability=== | ||

| − | If {<math>A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n</math>} | + | If {<math>A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n</math>} partition the sample space ''S'' (i.e., all events are mutually exclusive and <math>\cup_{i=1}^n {A_i}=S</math>) then for any event B |

<center><math>P(B) = P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2) + \cdots + P(B|A_n)P(A_n) | <center><math>P(B) = P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2) + \cdots + P(B|A_n)P(A_n) | ||

</math></center> | </math></center> | ||

| Line 95: | Line 117: | ||

* Example, if <math>A_1</math> and <math>A_2</math> partition the sample space (think of males and females), then the probability of any event B (e.g., smoker) may be computed by: | * Example, if <math>A_1</math> and <math>A_2</math> partition the sample space (think of males and females), then the probability of any event B (e.g., smoker) may be computed by: | ||

| − | <math>P(B) = P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)</math>. This of course is a simple consequence of the fact that <math>P(B) = P(B\cap S) = P(B \cap (A_1 \cup A_2)) = P((B \cap A_1) \cup (B \cap A_2))= P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)</math>. | + | <math>P(B) = P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)</math>. This of course is a simple consequence of the fact that <math>P(B) = P(B\cap S) = P(B \cap (A_1 \cup A_2))</math>. Therefore, |

| + | <math>P(B)=P((B \cap A_1) \cup (B \cap A_2))= P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)</math>. | ||

===Bayesian Rule=== | ===Bayesian Rule=== | ||

| − | If {<math>A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n</math>} | + | If {<math>A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n</math>} partition the sample space ''S'' and A and B are any events (subsets of S), then: |

<center><math>P(A | B) = {P(B | A) P(A) \over P(B)} = {P(B | A) P(A) \over P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2) + \cdots + P(B|A_n)P(A_n)}.</math></center> | <center><math>P(A | B) = {P(B | A) P(A) \over P(B)} = {P(B | A) P(A) \over P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2) + \cdots + P(B|A_n)P(A_n)}.</math></center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Independence vs. disjointness/mutual-exclusiveness=== | ||

| + | : The events A and B are ''independent'' if P(A|B)=P(A). That is <math>P(A \cap B) = P(A)P(B).</math> | ||

| + | : The events C and D are ''disjoint, or mutually-exclusive'', if <math>P(C\cap D) = 0</math>. That is <math>P(C\cup D)=P(C)+P(D).</math> | ||

| + | Mutual-exclusiveness and independence are different concepts. Here are two examples clarifying the differences between these concepts: | ||

| + | ====Card experiment==== | ||

| + | Suppose we play a [[SOCR_EduMaterials_Activities_CardExperiment | card game]] of ''guessing the color of a randomly drawn card'' from a [[AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Simul#Poker_Game |standard 52-card deck]]. As there are 2 possible colors (black \(\clubsuit, \spadesuit\) and red \(\color{red}\heartsuit, \color{red}\diamondsuit\)), and given no other information, the chance of correctly guessing the color (e.g., black) is 0.5. However, additional information may or may not be helpful in identifying the card color. For example: | ||

| + | * If we know that the [[AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Count#Hands-on_combination_activity |card denomination]] is a king, and there are 2 red and 2 black kings, this does '''not''' help us improve our chances of successfully identifying the correct color of the card, P(Red|King)=P(Red), independence. | ||

| + | * If we know that the suit of the card is heart, this does help us with correctly identifying the card color (as heart is red), P(Red|Hearts)=1.0, strong dependence as P(Red)=0.5. | ||

| + | * Notes: | ||

| + | ** In both cases, the events A={Red} and B={King} and C={Hearts} are '''not''' mutually exclusive (disjoint). | ||

| + | ** Events that are mutually exclusive (disjoint) cannot be independent. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Colorblindness experiment==== | ||

| + | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_blindness Color blindness] is a sex-linked trait, as many of the genes involved in color vision are on the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X_chromosome X chromosome]. Color blindness is more common in males than in females, as men do not have a second X chromosome to overwrite the chromosome which carries the mutation. If 8% of variants of a given gene are defective (mutated), the probability of a single copy being defective is 8%, but the probability that two (independent) copies are both defective is 0.08 × 0.08 = 0.0064. | ||

| + | * The events A={Female} and B={Color blind} are not mutually exclusive (females can be color blind), nor independent (the rate of color blindness among females is lower). Color blindness prevalence within the 2 genders is P(CB|Male) = 0.08, and P(CB|Female)=0.005, where CB={color blind, one color, a color combination, or another mutation}. | ||

| + | * See the [http://distributome.org/blog/?p=67 Distributome Colorblindness activity]. | ||

===Example=== | ===Example=== | ||

| Line 106: | Line 146: | ||

Denote D = {the test person has the disease}, <math>D^c</math> = {the test person does not have the disease} and T = {the test result is positive}. Then | Denote D = {the test person has the disease}, <math>D^c</math> = {the test person does not have the disease} and T = {the test result is positive}. Then | ||

<center><math>P(D | T) = {P(T | D) P(D) \over P(T)} = {P(T | D) P(D) \over P(T|D)P(D) + P(T|D^c)P(D^c)}=</math> | <center><math>P(D | T) = {P(T | D) P(D) \over P(T)} = {P(T | D) P(D) \over P(T|D)P(D) + P(T|D^c)P(D^c)}=</math> | ||

| − | <math>={0.95\times 0.005 \over {0.95\times 0.005 +0.01\times 0.995}}=0. | + | <math>={0.95\times 0.005 \over {0.95\times 0.005 +0.01\times 0.995}}=0.3231293.</math></center> |

===See also=== | ===See also=== | ||

| Line 119: | Line 159: | ||

* SOCR Home page: http://www.socr.ucla.edu | * SOCR Home page: http://www.socr.ucla.edu | ||

| − | {{translate|pageName=http://wiki. | + | "{{translate|pageName=http://wiki.socr.umich.edu/index.php?title=AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Prob_Rules}} |

Latest revision as of 14:23, 3 March 2020

Contents

- 1 General Advance-Placement (AP) Statistics Curriculum - Probability Theory Rules

- 1.1 Addition Rule

- 1.2 Conditional Probability

- 1.3 Examples

- 1.4 Inverting the order of conditioning

- 1.5 Example - inverting conditioning

- 1.6 Statistical Independence

- 1.7 Multiplication Rule

- 1.8 Law of total probability

- 1.9 Bayesian Rule

- 1.10 Independence vs. disjointness/mutual-exclusiveness

- 1.11 Example

- 1.12 See also

- 1.13 Problems

- 1.14 References

General Advance-Placement (AP) Statistics Curriculum - Probability Theory Rules

Addition Rule

Let's start with an example. Suppose the chance of colder weather (C) is 30%, chance of rain (R) and colder weather (C) is 15% and the chance of rain or colder weather is 75%. What is the chance of rain. This can be computed by observing that \(P(R \cup C) = P(R) + P(C) - P(R \cap C)\). Thus, \(P(R) = P(R \cup C) − P(C) + P(R \cap C)= 0.75 − 0.3 + 0.15 = 0.6\). How can this observation be generalized?

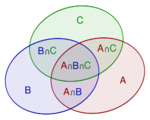

The probability of a union, also called the Inclusion-Exclusion principle allows us to compute probabilities of composite events represented as unions (i.e., sums) of simpler events.

For events A1, ..., An in a probability space (S,P), the probability of the union for n=2 is \[P(A_1\cup A_2)=P(A_1)+P(A_2)-P(A_1\cap A_2),\]

For n=3, \[P(A_1\cup A_2\cup A_3)=P(A_1)+P(A_2)+P(A_3) -P(A_1\cap A_2)-P(A_1\cap A_3)-P(A_2\cap A_3)+P(A_1\cap A_2\cap A_3)\]

In general, for any n, \[P(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_i) =\sum_{i=1}^n {P(A_i)} -\sum_{i,j\,:\,i<j}{P(A_i\cap A_j)} +\sum_{i,j,k\,:\,i<j<k}{P(A_i\cap A_j\cap A_k)}+ \cdots\] \[\cdots\ +(-1)^{m+1} \sum_{i_1<i_2< \cdots < i_m}{P(\bigcap_{p=1}^m A_{i_p})}+ \cdots\cdots\ +(-1)^{n+1} P(\bigcap_{i=1}^n A_i).\]

Conditional Probability

The conditional probability of A occurring given that B occurs is given by \[P(A | B) ={P(A \cap B) \over P(B)}.\]

Suppose X and Y are jointly continuous random variables with a joint density \(ƒ_{X,Y}(x,y)\). If A and B (non-trivial) are subsets of the ranges of X and Y (e.g., intervals), then:

- \( P(X \in A \mid Y \in B) = \frac{\int_{y\in B}\int_{x\in A} f_{X,Y}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}{\int_{y\in B}\int_{x\in\Omega} f_{X,Y}(x,y)\,dx\,dy}. \)

In the special case where B={y0}, representing a single point, the conditional probability is:

- \( P(X \in A \mid Y = y_0) = \frac{\int_{x\in A} f_{X,Y}(x,y_0)\,dx}{\int_{x\in\Omega} f_{X,Y}(x,y_0)\,dx}. \)

Of course, if the set (range) A is trivial, then the conditional probability is zero.

- See the example of the SOCR HTML5 Bivariate (2D) Normal Distribution Calculator (webapp).

- The conditional probability distribution of X given Y = \(y_0\), \(f_{X|Y=y_o}\), is given by:

- \( f_{X|y_o} \sim N \left ( \mu_{X|y_o} = \mu_X +\rho \frac{\sigma_X}{\sigma_Y}(y_o-\mu_Y), \sigma_{X|y_o}^2 = \sigma_X^2(1-\rho^2) \right) \), where

- \( X \sim N (\mu_X, \sigma_X^2) \),

- \( Y \sim N (\mu_Y, \sigma_Y^2) \), and

- \( \rho = Corr(X,Y)\) is the correlation between X and Y.

- This expression of the density assumes that the conditional mean of X given \(y_o\) is linear in y and the conditional variance of X given \(y_o\) is constant.

Examples

Contingency table

Here is the data of 400 Melanoma (skin cancer) Patients by Type and Site

| Type | Site | Totals | ||

| Head and Neck | Trunk | Extremities | ||

| Hutchinson's melanomic freckle | 22 | 2 | 10 | 34 |

| Superficial | 16 | 54 | 115 | 185 |

| Nodular | 19 | 33 | 73 | 125 |

| Indeterminant | 11 | 17 | 28 | 56 |

| Column Totals | 68 | 106 | 226 | 400 |

- Suppose we select one out of the 400 patients in the study and we want to find the probability that the cancer is on the extremities given that it is a type of nodular: P = 73/125 = P(Extremities | Nodular)

- What is the probability that for a randomly chosen patient the cancer type is Superficial given that it appears on the Trunk?

Monty Hall Problem

Recall that earlier we discussed the Monty Hall Experiment. We now show the odds of winning double if we use the swap strategy - that is the probability of a win is 2/3, if each time we switch and choose the last third card.

Denote W={Final Win of the Car Price}. Let L1 and W2 represent the events of choosing the donkey (loosing) and the car (winning) at the player's first and second choice, respectively. Then, the chance of winning in the swapping-strategy case is\[P(W) = P(L_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | L_1) P(L_1) = 1 \times {2\over 3} ={2\over 3}.\] If we played using the stay-home strategy, our chance of winning would have been\[P(W) = P(W_1 \cap W_2) = P(W_2 | W_1) P(W_1) = 1 \times {1\over 3} ={1\over 3},\] or half the chance in the first (swapping) case.

Drawing balls without replacement

Suppose we draw 2 balls randomly, one at a time without replacement from an urn containing 4 black and 3 white balls, otherwise identical. What is the probability that the second ball is black? Sample Space? P({2-nd ball is black}) = P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is black}) + P({2-nd is black} &{1-st is white}) = 4/7 x 3/6 + 4/6 x 3/7 = 4/7.

Inverting the order of conditioning

In many practical situations, it is beneficial to be able to swap the event of interest and the conditioning event when we are computing probabilities. This can easily be accomplished using this trivial, yet powerful, identity:

Example - inverting conditioning

Suppose we classify the entire female population into 2 classes: healthy(NC) controls and cancer patients. If a woman has a positive mammogram result, what is the probability that she has breast cancer?

Suppose we obtain medical evidence for a subject in terms of the results of her mammogram (imaging) test: positive or negative mammogram . If P(Positive Test) = 0.107, P(Cancer) = 0.1, P(Positive test | Cancer) = 0.8, then we can easily calculate the probability of real interest - the chance that the subject has cancer:

This equation has 3 known parameters and 1 unknown variable. So, we can solve for P(Cancer | Positive Test) to determine the chance the patient who has breast cancer given that her mammogram was positively read. This probability, of course, will significantly influence the treatment action recommended by the physician.

Statistical Independence

Events A and B are statistically independent. Even knowing whether B has occurred gives no new information about the chances of A occurring, i.e., if P(A | B) = P(A).

Note that if A is independent of B, then B is also independent of A, i.e., P(B | A) = P(B), since \(P(B|A)={P(B \cap A) \over P(A)} = {P(A|B)P(B) \over P(A)} = P(B)\).

If A and B are statistically independent, then \(P(B \cap A) = P(A) \times P(B).\)

Multiplication Rule

For any two events (whether dependent or independent):

In general, for any collection of events:

Law of total probability

If {\(A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n\)} partition the sample space S (i.e., all events are mutually exclusive and \(\cup_{i=1}^n {A_i}=S\)) then for any event B

- Example, if \(A_1\) and \(A_2\) partition the sample space (think of males and females), then the probability of any event B (e.g., smoker) may be computed by\[P(B) = P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)\]. This of course is a simple consequence of the fact that \(P(B) = P(B\cap S) = P(B \cap (A_1 \cup A_2))\). Therefore,

\(P(B)=P((B \cap A_1) \cup (B \cap A_2))= P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2)\).

Bayesian Rule

If {\(A_1, A_2, A_3, \cdots, A_n\)} partition the sample space S and A and B are any events (subsets of S), then:

Independence vs. disjointness/mutual-exclusiveness

- The events A and B are independent if P(A|B)=P(A). That is \(P(A \cap B) = P(A)P(B).\)

- The events C and D are disjoint, or mutually-exclusive, if \(P(C\cap D) = 0\). That is \(P(C\cup D)=P(C)+P(D).\)

Mutual-exclusiveness and independence are different concepts. Here are two examples clarifying the differences between these concepts:

Card experiment

Suppose we play a card game of guessing the color of a randomly drawn card from a standard 52-card deck. As there are 2 possible colors (black \(\clubsuit, \spadesuit\) and red \(\color{red}\heartsuit, \color{red}\diamondsuit\)), and given no other information, the chance of correctly guessing the color (e.g., black) is 0.5. However, additional information may or may not be helpful in identifying the card color. For example:

- If we know that the card denomination is a king, and there are 2 red and 2 black kings, this does not help us improve our chances of successfully identifying the correct color of the card, P(Red|King)=P(Red), independence.

- If we know that the suit of the card is heart, this does help us with correctly identifying the card color (as heart is red), P(Red|Hearts)=1.0, strong dependence as P(Red)=0.5.

- Notes:

- In both cases, the events A={Red} and B={King} and C={Hearts} are not mutually exclusive (disjoint).

- Events that are mutually exclusive (disjoint) cannot be independent.

Colorblindness experiment

Color blindness is a sex-linked trait, as many of the genes involved in color vision are on the X chromosome. Color blindness is more common in males than in females, as men do not have a second X chromosome to overwrite the chromosome which carries the mutation. If 8% of variants of a given gene are defective (mutated), the probability of a single copy being defective is 8%, but the probability that two (independent) copies are both defective is 0.08 × 0.08 = 0.0064.

- The events A={Female} and B={Color blind} are not mutually exclusive (females can be color blind), nor independent (the rate of color blindness among females is lower). Color blindness prevalence within the 2 genders is P(CB|Male) = 0.08, and P(CB|Female)=0.005, where CB={color blind, one color, a color combination, or another mutation}.

- See the Distributome Colorblindness activity.

Example

Suppose a Laboratory blood test is used as evidence for a disease. Assume P(positive Test| Disease) = 0.95, P(positive Test| no Disease)=0.01 and P(Disease) = 0.005. Find P(Disease|positive Test)=?

Denote D = {the test person has the disease}, \(D^c\) = {the test person does not have the disease} and T = {the test result is positive}. Then

See also

Problems

References

- SOCR Home page: http://www.socr.ucla.edu

"-----

Translate this page: